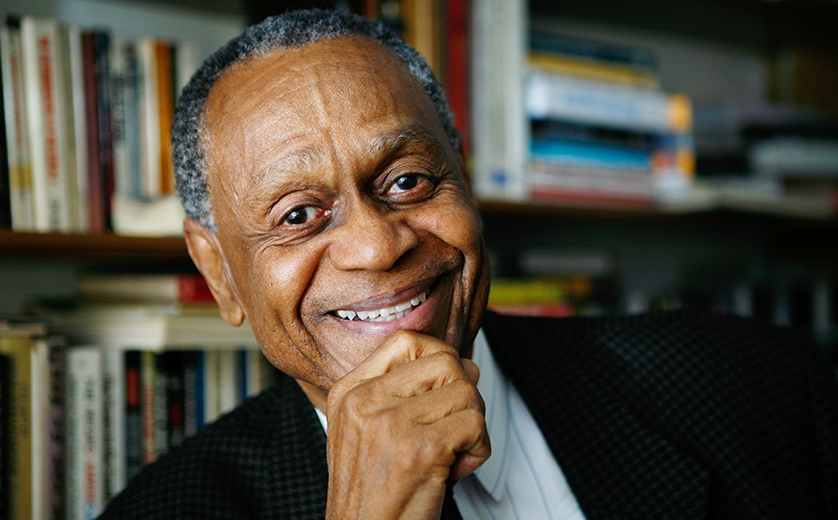

As Jack A. Kirkland marks his 50th year on the Brown School faculty, the issues that motivated his remarkable career in social work and civil rights are as urgent today as they were when he began. From his annual seminar that takes students to underserved neighborhoods, to his research on economic development in urban areas, Kirkland has sought to create change through understanding.

“What I teach is to how to change our thought processes in order to be able to walk in different cultures, and to deal with the African American urban struggle,” he says.

The result has been a legacy of research, public service and teaching, as well as an international reputation for enriching the experience of thousands of students, organizations, and state and municipal leaders who have sought his insights and advice.

“Jack Kirkland is an icon here at the Brown School and well beyond,” said Mary McKay, Neidorff Family and Centene Corporation Dean of the Brown School. “His achievements have benefited a large and diverse array of students, faculty and communities striving for concrete progress in social and racial justice in the United States and around the world.”

Kirkland joined the Brown School as an assistant professor in 1970 after teaching for several years at St. Louis University. Soon thereafter, he co-founded and chaired the Black Studies Program at Washington University (now the Department of African and African-American Studies). A popular teacher, he was three times voted Most Outstanding Teacher, at the university as well as the Brown School. He also received the Distinguished Faculty Alumni Award.

Now an associate professor, he is perhaps best known on campus for his field-based summer course, “Poverty – The Impact of Institutionalized Racism,” which immerses students in the community of East St. Louis and teaches them to strategize on policies that can combat the effects of urban blight and poverty. The summer course was canceled this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but Kirkland said he hopes to resume next summer.

“It’s an opportunity to watch students and engage them in the process of seeing individuals and families grow and excel and lift themselves up,” he said. “Students come into our school with a desire to help people who are disadvantaged. But many have very little knowledge about why families are trapped. What students come to discover is you can help people develop self-esteem and motivate themselves to change the situation they’re in and do what they can for oncoming generations.”

One of those students was Keaira Anderson, MSW ’15, the former executive director of the Cornerstone Community Development Corp. who continues to lead the effort for affordable housing in the West End neighborhood of St. Louis as a board member of Delmar Divine, a $100 million redevelopment project. Asked during a recent panel discussion about how the Brown School prepared her for her work, she immediately mentioned Kirkland and the summer course in East St. Louis.

“He talked a lot about making sure that once we graduate, we truly treat it as an extended practicum experience,” she said. “Now, I’m making sure I’m seeking to understand the needs, the strengths and the opportunities in communities. I truly do thank Professor Jack Kirkland for that experience.”

Another former student of Kirkland, Karen Stewart, MSW ’11, was raised in the majority-white community of Springfield, Mo. “Jack really helped me expand my world view in a way I didn’t even know needed expanding,” said Stewart, MSW ’11, who recalled that she initially argued with Kirkland’s views on race. “I said no one has given me anything,” she said. “He said, ‘I know you believe that.’” She said she soon realized the truth of Kirkland’s teaching, and he became her adviser.

“He said, ‘No one is poor in America because they’re white,’ and that is really accurate,” said Stewart who is now an adjunct faculty member at the Brown School and a consultant to organizations on issues of race. “The two questions he wants students to answer are: How can we help poor people? And, why are people poor? What Jack Kirkland does is not so much about social work as it is about social justice.”

Kirkland’s academic career was influenced by his vast array of work outside the classroom. One of the most significant experiences came in 1976, when Missouri Governor Joseph Teasdale appointed him as the state’s Director of Transportation. His two years in the cabinet position helped to transform his thinking about social work, and the economic impact of policy on the lives of communities. “I saw that economic development often had no conscience,” he said. “The gentrification, urban development and highway development destroyed many Black communities. Most of social work deals with services. But if you’re going to be working with people who are economically distressed, the thing that’s imperative is that it be about economic uplift.”

When he returned to the Brown School, he founded the concentration in Social and Economic Development and served as its chair for ten years. He said the Brown School remains the only school in the nation to offer a full concentration on the subject.

Kirkland’s teaching draws from his extensive life experience. Born during the Great Depression, he grew up in western Pennsylvania and attended Syracuse University, where he became the first African-American graduate of the School of Social Work and upon graduation was inducted into the Phi Delta Kappa Education Honorary Society.

He served as Director of Community Development for Peace Corps for Latin America, and has consulted with mayors across the nation about community development. Locally he became the first African American elected to the University City Board of Education, and was a consultant in the school desegregation decree for St. Louis and St. Louis County. He participated in research with scholars at Stanford University and the U.S. Department of Education that led to the department’s Charter Schools Program. He also consulted with the Department of Indian Affairs in Washington, testified before Congressional committees, was appointed to the executive board of the St. Louis County Economic Council, and served as a member of trade missions to Indonesia and China. Kirkland is a member of The History Makers, a non-profit research and educational institution committed to preserving and making accessible the untold personal stories of well-known and unsung African Americans.

His work has been recently acknowledged with the creation of the endowed Jack. A. Kirkland Scholarship for Social and Economic Development, in recognition of his impact and legacy at the Brown School. The scholarship will support students with significant financial need who are committed to working in Black communities. For more information or to make a gift in support, reach out to Brown School Advancement.

“My work has brought me to realize that the most impactful way to apply social work to economic development is by working directly with power structures,” he said. Most recently, he’s been a consultant to the mayors of three small St. Louis municipalities on a merger to help improve their economies. “My focus is how to help mayors put in place an economic baseline so they have an opportunity to see capital come through and show how people can help themselves and one another economically,” he said.

Now well into his ninth decade, Kirkland remains as passionate about his mission as ever, with few thoughts of retirement. “I’ll retire when I don’t have anything else to say that’s helpful for young people to hear,” he said.

Fortunately for Brown School students, that doesn’t appear to be happening any time soon.